The Life and Art of David Ohannessian

By Sato Moughalian

Stanford University Press, April 2019,

440 pages, US$ 30

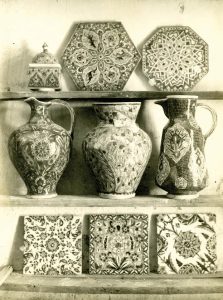

With this book, Sato Moughalian, a granddaughter of David Ohannessian, celebrates the centenary of one of Jerusalem’s most distinctive and popular arts, the brilliant glazed tiles and pottery known as Armenian ceramics. Founded in Palestine by David Ohannessian in 1919, this luminous art has its origins in fifteenth-century Ottoman Kütahya. At the peak of that city’s production, in the early eighteenth century, hundreds of local craftsmen, primarily Armenian, catered to the imperial taste for elaborately decorated wall tiles, vases, and tableware. Kütahya’s commerce declined in the nineteenth century, but the rise of Turkish nationalism at the turn of the century engendered a revivalist architectural style that emphasized archetypal components of the great Seljuk and Ottoman monuments – hemispheric domes, wide eaves, pointed arches, and of course, tiled facades.

By 1907, David Ohannessian had mastered Kütahya’s ceramic tradition and established an atelier there – the Société Ottomane de Faïence. He partnered on large commissions with the Minassian brothers and Mehmet Emin, who led the city’s two other workshops. After the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, architect Ahmet Kemalettin, a leading figure in the government’s modernizing efforts, commissioned all three Kütahya studios to create tiles for new buildings in Constantinople and for the renovations of important mosques and shrines in Bursa, Damascus, Mecca, Konya, Cairo, and the Ottoman capital. Renowned for his skill in historical restorations, Ohannessian also won the Gold Medal for his pottery in the 1910 Bursa Trade Fair and exported his wares to England and France.

In 1911, a fateful meeting changed the course of Ohannessian’s life. British diplomat Mark Sykes ventured to Kütahya seeking an artist to create a grand tiled chamber for his manor in Yorkshire, Sledmere House. Sykes commissioned Ohannessian. After his tiles were installed in early 1914, they were widely admired by Sir Mark’s fellow British military officers and Oxbridge friends, including Ronald Storrs.

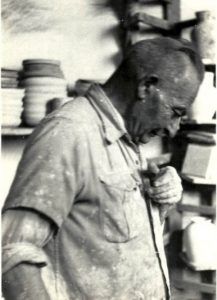

Photo: Ohannessian Family Collection.

The Great War brought devastation and famine to Palestine and large-scale massacre and expulsion of the Anatolian Armenians. Ohannessian was arrested in Kütahya in late 1915 and deported with his family toward the Syrian desert, eventually taking refuge in Aleppo. After the fall of the Ottomans, Sykes arrived in Aleppo and encountered Ohannessian. Knowing of Jerusalem Military Governor Ronald Storrs’s determination to restore the precarious tiling of the Dome of the Rock, Sykes recommended Ohannessian. Other officers who had seen Ohannessian’s tiles in Yorkshire concurred.

Photo: Ohannessian Family Collection.

Upon his arrival in Jerusalem at the end of 1918, Ohannessian met with Ernest T. Richmond, the British architect charged with evaluating the condition of Al-Aqsa’s structures. In mid-1919, Ohannessian returned briefly to Kütahya. He recruited a small group of ceramists, including Mgrditch Karakashian and Nishan Balian, each one highly skilled in a different facet of the art. Collaborating with Near East Relief, Ohannessian also trained scores of Armenian orphans in his new workshop on the Via Dolorosa.

Jerusalem, ca. 1920.

Photo: American Colony Photo Dept., Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

In 1922, Balian and Karakashian left to found their own joint studio on Nablus Road.

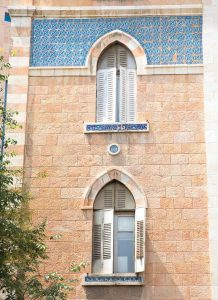

Ohannessian developed a flourishing trade in pottery noted for its intense greens and blues. In the 1920s and 1930s, he carried over to Jerusalem the Ottoman tradition of ornamenting building facades, working with architects Spyro Houris, Nikephoros Petassis, and Maurice Gisler, who designed villas and apartment houses for prominent Arab families. He exhibited in prestigious international expositions in Europe as well as the 1933–1934 Chicago World’s Fair.

Photo by Orhan Kolukısa.

Charles Ashbee and the Pro-Jerusalem Society commissioned Ohannessian to make tile panels for the Citadel Garden and trilingual ceramic street signs in the Old City. British architects Austen St. Barbe Harrison and Clifford Holliday incorporated Ohannessian’s tile designs in St. Andrew’s Church, the British and Foreign Bible Society, St. John’s Ophthalmic Hospital, a grand fireplace for the High Commissioner’s residence, and a tiled fountain niche for the Palestine (Rockefeller) Archaeological Museum.

Today, descendants of the families that Ohannessian brought to Palestine in 1919 continue to create and enlarge this extraordinary art, managing two successful enterprises – Balian Armenian Ceramics on Nablus Road and Karakashian Jerusalem Pottery on Greek Orthodox Patriarchate Street. Other families, notably, the Sandrouni brothers, Vic Lepejian, and Hagop Antreassian have also joined in, creating new branches of this venerable art and ensuring that Armenian Jerusalem ceramics will thrive long into the future.

Sato Moughalian is a prize-winning flutist in New York City and artistic director of Perspectives Ensemble.