Translated from Arabic by Rania Filfil

Several times have I crossed the street near the place where the British Forces used to administer the city. Every time, I remember Rowan Atkinson, the international actor known for playing the character Mr. Bean, and how he deposited an envelope into a classical mailbox in one of his famous comic episodes. But the street I usually take is only a side street now that leads to the Nablus Municipal Library, one of the oldest public libraries in Palestine, which hosts the famous room with the city’s archives. It has been 70 years since the British Forces withdrew from Nablus, but their traces remain. One of them is a mailbox, similar to the one in which Mr. Bean deposits his letter. It carries a sign that is engraved in iron and reads Great Britain, the United Kingdom.

The last time I crossed the street, heading to the archive hall in the library to search for telegrams and letters from that era, I found the box completely neglected, surrounded by piles of rubbish and a group of kids who wanted to post letters. They filled its opening with letters and papers torn from school notebooks of the last academic semester.

With this mailbox, the British did not bring anything new to this country; they merely changed the tools that were used to transport mail and installed many similar boxes to carry political and personal letters from the world to Palestine and vice versa.* Mail first appeared under Sargon, the Akkadian ruler who governed Palestine in the twenty-second century BC. At that ancient time, mail passed through Palestine to travel to the empires of the Orient.

On the afternoon when I saw the mailbox being filled with school papers, it was pouring rain in Nablus, the historic city that was established by the Canaanites and targeted by many rulers and armies. To protect myself, I entered the historical Humoz Café at whose entrance the box is found. This same café used to be a meeting point for the British forces that occupied it to turn it into a base for its military musical band, with officers from different ranks that governed the troops in the city. From this very place, officers, soldiers, and other people used to send and receive letters through the box that was only a few steps away from their seats. Even though the café has been modernized, the smell of these old letters lingers, and just across the street is the archive room of the library building.

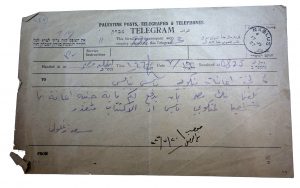

In the archive room, I found Dr. Ameen Abu Baker, a professor of modern history specialized in the era of late Ottoman rule and the British Mandate. He was wandering among old letters and telegrams that had arrived in Palestine at that time, many decades ago. Dr. Abu Baker greeted me as I entered the archive room, and he happened to be carrying a telegram sent by Saad Zaghlol, the historical Egyptian figure and leader of the 1919 revolution in Egypt, to the city of Nablus on July 17, 1927. The letter was sent after an earthquake in the city, and he promised to donate 100 Egyptian pounds to relieve the afflicted population. That telegram, along with many other letters, had been delivered through the British mailboxes as an expression of regional and local support to the city after the historic earthquake.

The Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry’s 1945 report on the number of letters carried in the period from 1924 to 1944 indicates that Palestinians sent and received 10,626,000 letters per year; the number increased to 46,326,400 letters in the year 1944!

On that day, Dr. Abu Baker told me much about the means of communication in that period, as narrated by the historian Joseph Walker. The ladies who work in the archives department contributed and spoke proudly of the rich history of the city. The first telegram arrived in Palestine in 1862; it was then called the Egyptian Telegraph. A year later, Jerusalem was connected to the telegraph, and according to Dr. Abu Baker, the Egyptian telegraph columns are still standing between Jerusalem and Jaffa to this day.

Palestinians were affected by the telegraph up to the most minute details of their lives. Telegrams opened up connections to the world and its trading circles. I had not been aware of this until Dr. Abu Baker presented me with statistics about the number of telegrams sent and received in Tulkarem on melon trading alone. I was astonished to learn that they had reached 100,000 telegrams by 1948.

Ottoman post offices had been located throughout historic Palestine, including in Nablus. It appears that in Palestine, the post and telecommunication sector was more developed than in other countries at the time. The telegraph service in Jaffa began in 1862. From Nablus, mail was transported to Jaffa in a special horse-drawn cart. It took six months to deliver the mail and receive a response from abroad. Afterwards, it was replaced by a train that reduced the response time from abroad to only two months. The situation stayed as such, according to Dr. Abu Baker, until telephone lines were established. The first telephone call between Palestine and the outside world took place in 1910 when the Ottoman Sultan talked to his administration in the City of Jerusalem.

Telephone service in Palestine is another interesting story. I had left the archive room and moved to the Qadri Touqan Library that is also located in the public library. Qadri Touqan was an Arab writer and intellectual. Later in life he became a politician who served as foreign minister to the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. He was born in Nablus in 1910, the same year in which the first international telephone communication with Jerusalem took place. His library and the room that hosts it were donated in their entirety to the municipality. It holds a unique treasure in the copy of a report prepared by the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry on surveying Palestine (the Survey of Palestine is a three-volume survey of Mandatory Palestine that was prepared between December 1945 and March 1956, as evidence for the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry). The report shows the development of the telecommunication sector in Palestine, with tables that monitored every phone call that was placed. The figures are stunning!

The sheer number of calls that were placed and letters posted made me wonder about the talks behind these calls – the regular calls and not the political and military calls made between Palestine and Britain. I trust that these latter calls paved the way for the current situation in Palestine and the continuation of the occupation. As a result, we lost the capacity to determine the fate of a letter that comes into or exits Palestine through the crossing points controlled nowadays by the Israeli authorities, the heirs of the British Forces’ legacy.

Three weeks earlier, Ilan Pappé, the famous Jewish historian had visited the city. He stopped opposite the mailbox but did not notice it. But as soon as he arrived in town, some of the city’s men showed him the archive room. He shook his head as he was leaving. I asked him about the Palestine Studies Program he administers at Exeter University in Britain and what researchers write about Palestine’s transition from the English to the Israeli occupation. Also present was Gabriel Poly, Pappé’s devoted student who specializes in this period as well. In front of a small audience, Pappé said that the acts of Britain cannot be isolated from the circle that served to create the state of Israel. At that moment, all these calls in the Anglo-American Inquiry Committee report rushed into my head. How many of these came from Britain? How many of the letters received here were behind what we live now?

After the last time I passed the mailbox, I asked Poly, “Is it true that the third (country) in which telecommunication between Britain and the outside world was established was Palestine?” Indeed, it came after Australia and South Africa. I sent him a recently published rigorous research study from the University of Glasgow referring to this piece of information.

Telephone headsets were picked up millions of times between 1924 and 1944 to pass on personal messages or military, administrative, and government orders. In 1924, 7.4 million local phone calls were made in Palestine, and in 1944, the number increased to 42,072,000. The report shows that the Palestinian government invested 1,311,360 Sterling pounds in the telecommunication sector and generated profits of 642,172 pounds.

He explained: “Telecommunication in Palestine started with this famous call by the head of the Ottoman Empire and bore the number “1” – a single-digit number but also an indicator of the person originating the call – the Sultan himself, in other words, the Number One person in the Empire. It remains impressive compared to 838 million phone calls made by the Palestinians in 2017, according to official statistics.

* Joseph Walker, How They Carried the Mail: From the Post Runners of King Sargon to the Air Mail of Today, University of California, 1930.