The year 2018 marks the 70th commemoration of the Palestinian Nakba. At the beginning of the twentieth century, most Palestinians lived inside the borders of “historical” or “Mandate Palestine,” now the State of Israel and the occupied Palestinian territory (the West Bank, including East Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip). Five major periods of forcible displacement transformed Palestinians into one of the largest and the longest-standing unresolved refugee cases in the world today.i

Zionist leaders established the Zionist movement in the late nineteenth century with the aim of creating a Jewish home through the formation of a “…national movement for the return of the Jewish people to their homeland and the resumption of Jewish sovereignty in the Land of Israel.”ii

As such, the Zionist enterprise combined Jewish nationalism – which it aimed to create and foster – with the colonial project of transplanting people who came mostly from Europe into Palestine, drawing on the support of European imperial powers. The Zionist movement constructed a specific global Jewish national identity in order to justify the colonization of Palestine. This identity had to be linked to Jewish presence in Palestine during the first century BC. Basically, the movement had to define the “Jewish people” as a national identity. As Ilan Pappe rightly concludes, “Zionism was not… the only case in history in which a colonialist project was pursued in the name of national or otherwise noncolonialist ideals.”iii

The task of establishing and maintaining a Jewish state on a predominantly non-Jewish territory has been carried out by forcibly displacing the non-Jewish majority population. Today, nearly 70 percent of the Palestinian people worldwide are themselves, or the descendants of, Palestinians who have been forcibly displaced by the Israeli regime.iv The idea of “transfer” in Zionist thought has been rigorously traced by Nur Masalha in his seminal text Expulsion of the Palestinians: The Concept of “Transfer” in Zionist Political Thought, 1882–1948, and is encapsulated in the words of Israel Zangwill, one of the early Zionist thinkers who, in 1905, stated, “If we wish to give a country to a people without a country, it is utter foolishness to allow it to be the country of two peoples.”v Yosef Weitz, former director of the Jewish National Fund’s Lands Department, was even more explicit when, in 1940, he wrote, “…it must be clear that there is no room in the country for both peoples (…) the only solution is a Land of Israel, at least a western Land of Israel without Arabs. There is no room here for compromise. (…) There is no way but to transfer the Arabs from here to the neighboring countries (…) Not one village must be left, not one (Bedouin) tribe.”vi Rights and ethics were not to stand in the way, or as David Ben-Gurion argued in 1948, “The war will give us the land. The concepts of ‘ours’ and ‘not ours’ are peace concepts, only, and in war they lose their meaning.”vii

The essence of political Zionism, therefore, is aptly summarized as the creation and fortification of a specific Jewish national identity, the takeover of the maximum amount of Palestinian land, and the assurance that the minimum number of non-Jewish persons remain on that land while the maximum number of Jewish nationals are implanted upon it. In other words, political Zionism from its inception has necessitated population transfer, notwithstanding its brutal requisites and consequences.

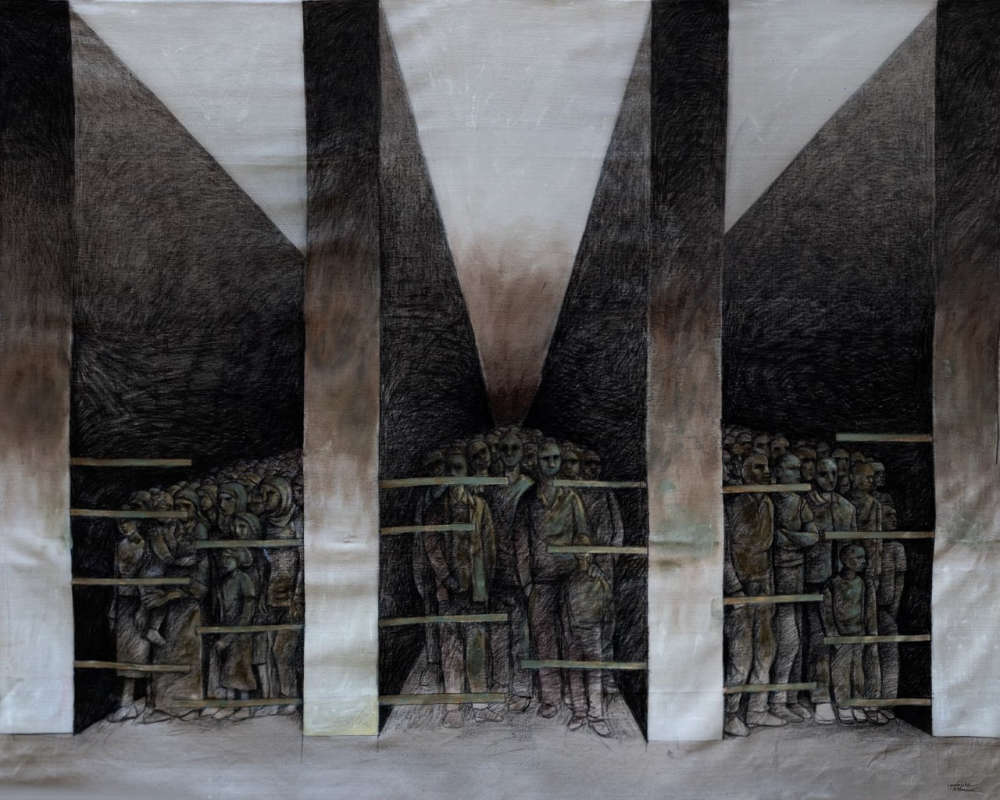

© Patrick Kruse/OPGAI.

The Zionist movement, when setting the scene to colonize Palestine in 1897 under the motto, “a land without a people for a people without a land,” faced three major obstacles: indigenous Palestinian people were living in the specified territory; Palestinians held property and land rights within this territory; and there was an insufficient number of Jewish people living in this territory. Various strategies were used in order to tackle these obstacles, including privileged migration for persons of Jewish origin, the targeted withdrawal of property rights from Palestinians, and forced population transfer.

After the establishment of Israel and in order to augment the number of Jewish people in the territory, Israel legislated the Law of Return (1950). The state created a system of privileged migration by declaring that every Jewish person in the world is entitled to Jewish nationality and can immigrate to Israel and acquire Israeli citizenship. Thus Jewish nationals enjoy the right to enter Israel even if they were not born in Israel and have no connection whatsoever to that state. In contrast, Palestinians, the indigenous population of the territory, are excluded from the Law of Return and have no automatic right to enter the country. The Law of Return has aimed to simplify and encourage the immigration of Jewish persons to Israel in order to achieve the exclusive Jewish state envisioned by Zionism.

In 1950, Israel legislated and deployed the Absentee Property Law to address the issue of Palestinian property rights, in other words, in order to confiscate Palestinian property legally owned by forcibly displaced Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons. The term “absentee” was defined so broadly as to include not only Palestinians who had fled the newly established State of Israel but also those who had fled their homes yet remained within its borders.viii Once confiscated, this land became state property.ix In 1953, Israel enacted the Land Acquisition Law to complete the transfer of confiscated Palestinian land, which had not been abandoned during the attacks of 1948, to the state. In the words of former Israeli Finance Minister Eliezer Kaplan, its purpose “…was to instill legality in some acts undertaken during and following the war.”x An almost identical process took place in the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) in the aftermath of the 1967 occupation.xi

Moreover, the expansion of existing Palestinian localities in Israel and the oPt has been severely curtailed as a result of Israel’s highly discriminatory planning policy. Since the occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip in 1967, Israel has not permitted the establishment of any new Palestinian municipalities, with the exception of the city of Rawabi. Military Order 418 created a planning and building regime which gives the Israeli state full control of all areas related to planning and development in the oPt.xii

The central obstacle to the Zionist movement, the Palestinian people themselves, has been addressed by various means throughout the last decades, resulting in forced population transfer. More than seven million Palestinians – including the descendants of the 700,000 persons who were expelled in 1948 – have been forcibly displaced from their homes. Israeli laws such as the Prevention of Infiltration Law (1954) and military orders 1649 and 1650 have prohibited Palestinians from legally returning to Israel or the oPt.xiii

A solution to the conflict would necessarily include:

– Recognition of the rights of all involved parties, in particular the Palestinian people’s right to self-determination; and the right of refugees and internally displaced persons to reparation (voluntary return, property restitution, and/or compensation).

– Addressing the root causes of the conflict: most importantly, forced population transfer.

– Ensuring rights for all parties and victims without discrimination.

– Setting the foundations of peaceful and cooperative relations between people, groups, individuals, and states. This would be an intrinsic component of a just peace and is essential for reconciliation, which in turn would be achieved through implementing transitional justice (both judicial and non-judicial) mechanisms and tools, including criminal prosecution, reparations, institutional reform, and truth commissions.

As illustrated by Nur Masalha, between 1930 and 1948 the Zionist movement planned for the forcible transfer of the indigenous Palestinian population in nine different strategies, starting with the 1930 Weizmann Transfer Scheme and continuing up to Plan Dalet, which was carried out in 1948.xiv However, forced displacement of the indigenous Palestinian people did not end with the establishment of Israel in 1948, rather it began that year. Since the 1948 Nakba, almost every passing year has witnessed a wave of forced displacement, albeit in varying degrees. While 400,000 Palestinians became refugees in 1967, in 2008, Israel revoked the residency rights of nearly 5,000 Palestinian Jerusalemites.xv

Today, this population transfer is carried out by Israel in the form of the overall policy of silent transfer. This displacement is silent in the sense that Israel carries it out while trying to avoid international attention, displacing small numbers of people on a weekly basis. It is to be distinguished from the more overt transfer achieved under the veneer of warfare in 1948. But the result is nevertheless a silent ongoing Nakba.

This Israeli policy of silent transfer is evident in the state’s laws, policies, and practices. Israel uses its power to discriminate, expropriate, and ultimately effect the forcible displacement of the indigenous non-Jewish population from the area of Palestine. For instance, the Israeli land-planning and zoning system has forced 93,000 Palestinians in East Jerusalem to build without proper construction permits because 87 percent of that area is off-limits to Palestinian use; most of the remaining 13 percent is already built up.xvi Since the Palestinian population of Jerusalem is growing steadily, it has had to expand into areas not zoned for Palestinian residence by the State of Israel. All these homes are now under the constant threat of being demolished by the Israeli army or police, which will leave their inhabitants homeless and displaced.

The Israeli Supreme Court bolstered the Zionist objective of clearing Palestine of its indigenous population in its 2012 decision prohibiting family unification between Palestinians with Israeli citizenship and their counterparts across and beyond the 1949 Armistice Line (or the 1967 Green Line). The effect of this ruling has been that Palestinians with different residency statuses, such as Israeli citizen, Jerusalem ID, West Bank ID, or Gaza ID (all of which are issued by Israel), cannot legally live together on either side of the 1949 Armistice Line. They are thus faced with the choice to live abroad, to live apart from one another, or to take the risk of living together illegally. This system aims to further diminish the Palestinian population. This demographic intention is reflected in the High Court’s explanation that “…human rights are not a prescription for national suicide.”xvii

According to the Israeli land-planning and zoning system, 87 percent of Jerusalem is off-limits to

Palestinians, forcing them to build without proper construction permits.

To secure a way forward that equally respects the rights of all parties involved, this Israeli system must be judged in accordance with international law and standards. In fact, the ongoing disrespect for international law in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict undermines the very legitimacy of this crucial body of legal instruments, in particular human rights, humanitarian law, and international criminal law. Therefore, it is time to ensure that international law is not merely a paper tiger but a legal system that protects rights, establishes obligations, and, most importantly, creates realities in accordance with its values and principles. A solution to the ongoing Nakba should be found through a strict rights-based approach. Such rights are not guaranteed through political negotiations but through full adherence to and implementation of international law and rights. Simply speaking, peace cannot be achieved when fundamental human rights and freedoms are violated.

In the case of Palestine, this approach would entail solutions based on international law rather than on political negotiations to bring about a long-lasting and just solution. In this light, it should be unacceptable to refer to the illegal Israeli settlements in the occupied Palestinian territory as “undermining efforts towards peace” – as is regularly the case in political circles – whilst in reality these settlements constitute a violation of numerous international standards and principles. As such, they represent a manifestation of Israel’s ongoing impunity, and therefore the implementation of international law and standards should not be subject to negotiations but demanded from the outset.

i Amjad Alqasis and Nidal al-Azza, Forced Population Transfer – The Case of Palestine: Introduction, BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights, 2014.

ii Mitchell Geoffrey Bard and Moshe Schwartz, 1001 Facts Everyone Should Know about Israel, Rowman & Littlefield, 2005.

iii Ilan Pappe, “Zionism as Colonialism: A Comparative View of Diluted Colonialism in Asia and Africa,” South Atlantic Quarterly 107:4, Fall 2008, p. 612.

iv BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights, Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons Survey of 2013–2015, BADIL, 2015.

v Nur Masalha, Expulsion of the Palestinians: The Concept of “Transfer” in Zionist Political Thought, 1882–1948, Institute for Palestine Studies, 1992, p. 10.

vi Benny Morris, 1948 and After: Israel and the Palestinians, Oxford University Press, 1994, p. 121.

vii Masalha, p. 180.

viii Geremy Forman and Alexandre Kedar, “From Arab Land to ‘Israel Lands’: The Legal Dispossession of the Palestinians Displaced by Israel in the Wake of 1948,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, Vol 22 (2004), p. 814.

ix See Salman Abu Sitta, “Dividing War Spoils: Israel’s Seizure, Confiscation and Sale of Palestinian Property,” August 2009, available at: http://www.plands.org/store/pdf/Selling%20Refugees%20Land.pdf.

x Forman and Kedar, p. 814.

xi Souad Dajani, Ruling Palestine – A History of the Legally Sanctioned Jewish-Israeli Seizure of Land and Housing in Palestine, COHRE and BADIL, 2005, p. 78.

xii See Alon Cohen-Liftshitz and Nir Shalev, The Prohibited Zone: Israeli Planning Policy in the Palestinian Villages in Area C, Bimkom, Jerusalem, 2008.

xiii Al-Haq, “Al-Haq’s Legal Analysis of Israeli Military Orders 1649 & 1650: Deportation and Forcible Transfer as International Crimes,” April 2010, available at: http://www.alzaytouna.net/english/Docs/2010/Al-Haq-April2010-Legal-Analysis.pdf.

xiv Ibid, p. 140.

xv United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), Jerusalem (OCHA 2011).

xvi OCHA, Demolitions and Forced Displacement in the Occupied West Bank, OCHA, 2012.

xvii Ben White, “Human rights equated with national suicide,” Al Jazeera, January 12, 2012, available at http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2012/01/20121121785669583.html.