Siham Rashid

Majd Beltaji

In Palestine, as in any national context, public policies are meant to provide the legal, regulatory, and judicial guidelines, accompanied by the financial commitments, to address issues that benefit the lives of all people in society. Unfortunately, all too often, nearly half the citizens are left out of the equation: women and girls. Palestine is no exception. The commitments are articulated, and (international and national) legal frameworks are endorsed, but there is a burgeoning gap between these national strategies and the reality that women and girls face in Palestinian society. To bridge this gap, we must work to eliminate the institutional and structural barriers that cause or perpetuate gender discrimination and inequalities in our society. A first critical step in this direction is two-fold: to ensure that the government designs policies that allow women and men to determine their own roles in society, and to hold the government accountable for implementation. As the National Policy Agenda (2017–2022) states, the government will focus on putting its citizens first. We citizens, women and men, must then support the government to achieve this aim.

Gender equality remains a priority for the State of Palestine, as reflected in the current National Policy Agenda, the accession to the Convention on Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and other international human rights treatiesi in 2014; the Cross-Sectoral National Gender Strategy 2017–2022, and the National Strategy to Combat Violence against Women 2011–2019. By acceding to CEDAW, the State of Palestine has assumed legal obligations to ensure the equal rights of men and women and the protection of women’s human rights. Nevertheless, as reported by the Independent Commission for Human Rights (ICHR) and civil-society organizations, national legislation is required for the incorporation of CEDAW provisions and other international agreements in order to regulate the merger of these treaties in the national legal system.

ICHR argues that “the socio-cultural, economic, and political reality for Palestinian women is one where discrimination and gender inequality remain pervasive and women do not enjoy the same rights as men.”ii The ICHR also notes that these gaps emanate from power relations, including gender-blind legislation.iii

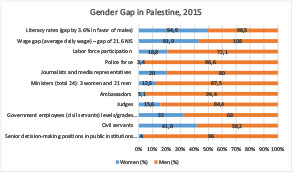

Gender-blind policies risk the perpetuation of further oppression and undermine the realization of gender equality. The chart below illustrates the findings of an ICHR and PCBS (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics) reportiv on the status of women in public life.

A recent survey, the International Men and Gender Equality Survey (IMAGES) in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA),v found that in Palestine “men and women appear to hold more positive views of women’s rights and equal roles in the public sphere than in private life.”vi However, the above-mentioned statistics indicate that the participation of women in public life and their employment status remain low. While the literacy rate and other gains have been achieved by women and girls, these have yet to translate into greater empowerment and participation in public life.

It is therefore vital that these gaps be addressed through a range of multidimensional initiatives – from focusing on changing gender norms and practices to eliminating discriminatory laws and public policies. This, however, cannot be achieved by one institution or entity alone. It takes many actors to craft opportunities and create an environment for women’s inclusion and influence in the public sphere. From the household and school to the office and ministries, men and women must work collectively to bring about gender equality.

While there are actors working to amend existing discriminatory laws, produce academic reports, and provide services and advocacy for change, there is no one body that conducts analysis and produces evidence-based gender-policy recommendations and briefs. Moreover, there is an absence of progress reporting on policy implementation and how policies affect (negatively or positively) women. Thus, nobody provides recommendations on how to follow up on and improve or refocus gender-equality policies. In the absence of an active facilitator for policy discourse on gender equality, there is no “safe space” to have such a debate. The consequent lack of coordination and follow-up contributes to the accountability gap.

It is clear that there is ample space and consensus for policies to improve gender equality in Palestine, and although traditions and customs play a critical role in the hindrance of this achievement, the IMAGES MENA study shows that the more prevalent problem is institutional – that inequalities are at times perpetrated from the highest levels of authority, the duty-bearers. This is where the Gender Policy Institute (GPI) comes in. Initiated in 2016, GPI is presently under the management of UNESCO and funded by the Government of Norway; it is in the final stages of becoming an independent national entity. The GPI builds on and advances the work of the Palestinian Women’s Research and Documentation Center, a program of UNESCO that was implemented from 2006 to 2015.

GPI works in partnership with the ministry of women’s affairs (MoWA) and governmental institutions (whole-of-government), and in close coordination with policy makers, practitioners, academics and academic institutions, the private sector, and others in order to create change and challenge policy direction through evidence-based data and information. In this context, GPI will conduct quantitative and qualitative analyses of gender-equality policies that contribute to shaping the policy debate in Palestine so that in 2018 and beyond, GPI’s products and services will result in policies that contribute to gender equality and an environment that is conducive to women’s empowerment.

Ms. Siham Rashid is the Executive Director of the Gender Policy Research Institute (GPI)/UNESCO and holds an MSc in public policy and management from the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London.

Ms. Majd Beltaji is the Gender Equality Programme Specialist at UNESCO Ramallah Office, and holds an MA in international cooperation and development and a BA in political science and media.

i The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), Convention Against Torture (CAT), Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), and the International Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (ICERD).

ii Independent Commission for Human Rights (2016), Fact Sheet: Discrimination and Inequality Gap in Gender Rights. See http://ichr.ps/en/1/17/1541/Sheet-of-Facts-Discrimination-and-Inequality-Gap-in-Gender-Rights.htm.

iii Ibid.

iv Independent Commission for Human Rights, Annual Report 2015, http://ichr.ps/en/1/6/1941/ICHR-21st-Annual-Report.htm pp. 93–95 and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (2016) Press Release: http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/portals/_pcbs/PressRelease/WomenDy2016E.pdf.

v International Men and Gender Equality Survey (IMAGES) conducted in four countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), including Palestine in 2017.

vi Promundo and UN Women (2017), IMAGES MENA, retrieved from (page 212): https://imagesmena.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2017/05/IMAGES-MENA-Multi-Country-Report-EN-16May2017-web.pdf.