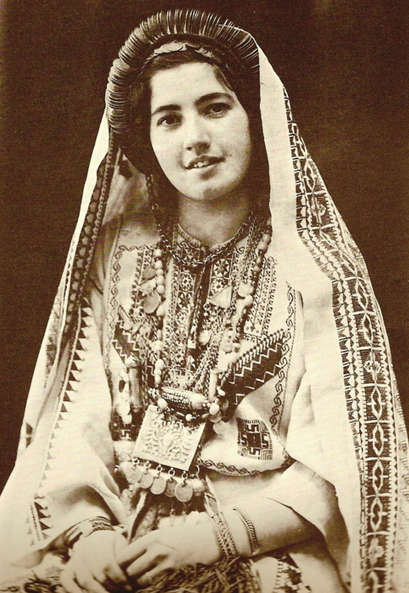

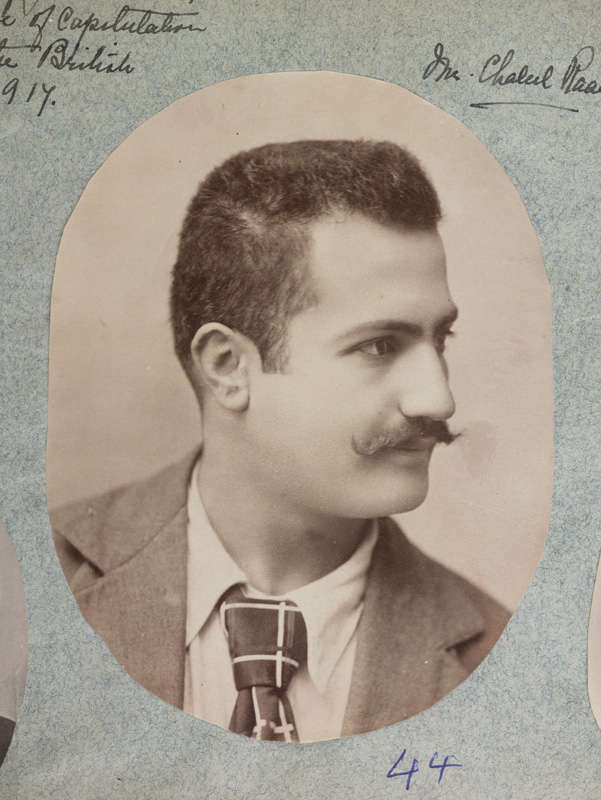

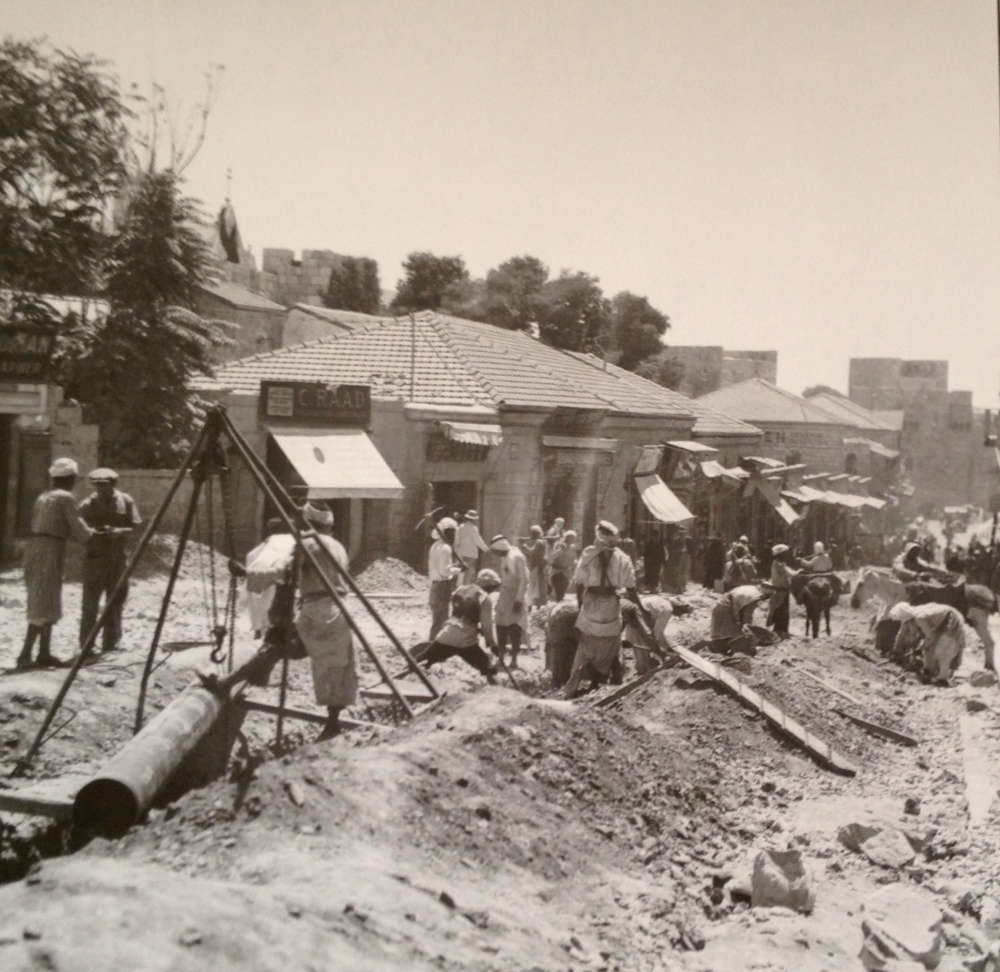

A woman in traditional dress bites her head cover and smiles widely at the camera while cradling a child; taxis line up in front of Damascus Gate in Jerusalem; a laborer in a citrus orchard loads oranges into baskets on the backs of two children; a view of Tiberias with Upper Mosque in the foreground; Prince Fuad and Ahmad Jamal Pasha visit Al-Haram al-Sharif: all are images that represent the breadth of subjects of Palestine’s first Arab photographer, Khalil Raad.

Raad was born in Bhamdoun, Lebanon, in 1854. When his father, a Maronite convert to Protestantism, was killed in 1860, his mother took Khalil and his sister to Jerusalem to live with relatives.

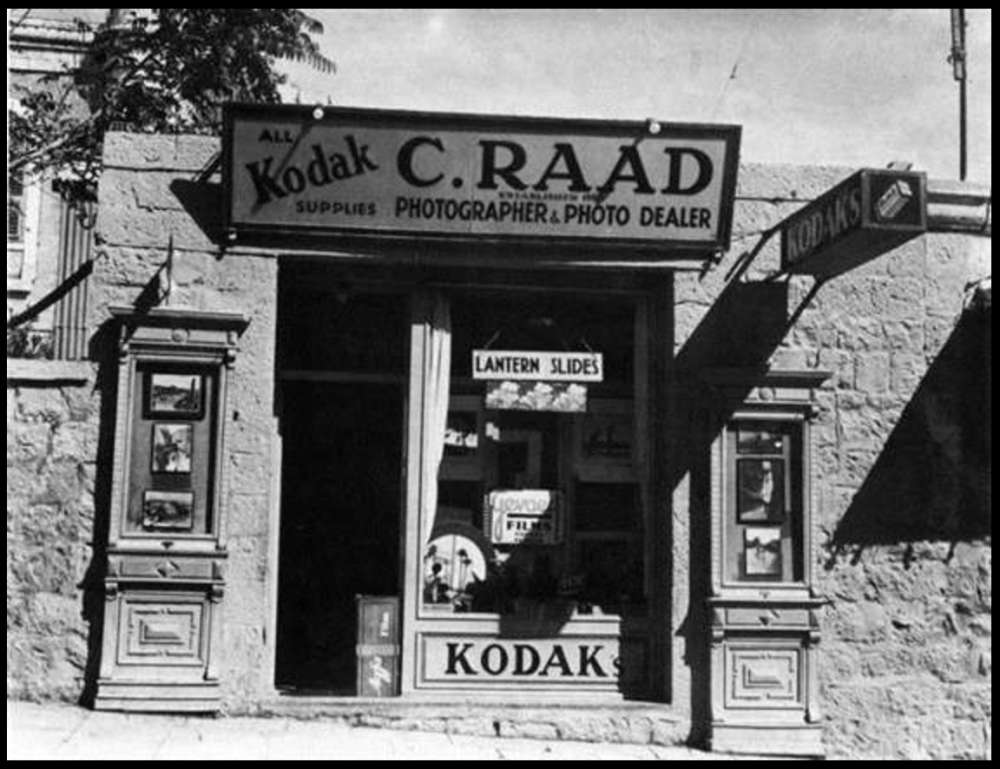

Around that time the nascent art of photography was finding local expression in Palestine through the efforts of the Armenian Patriarch in Jerusalem who offered training to youngsters. One student, Garabed Krikorian, arguably the first Palestinian to make photography his profession by opening a studio outside Jaffa Gate, took on Raad as an apprentice. In 1890, Raad engaged in direct competition with Krikorian when he started his own studio opposite his master’s, a move which sparked years of rivalry and animosity.

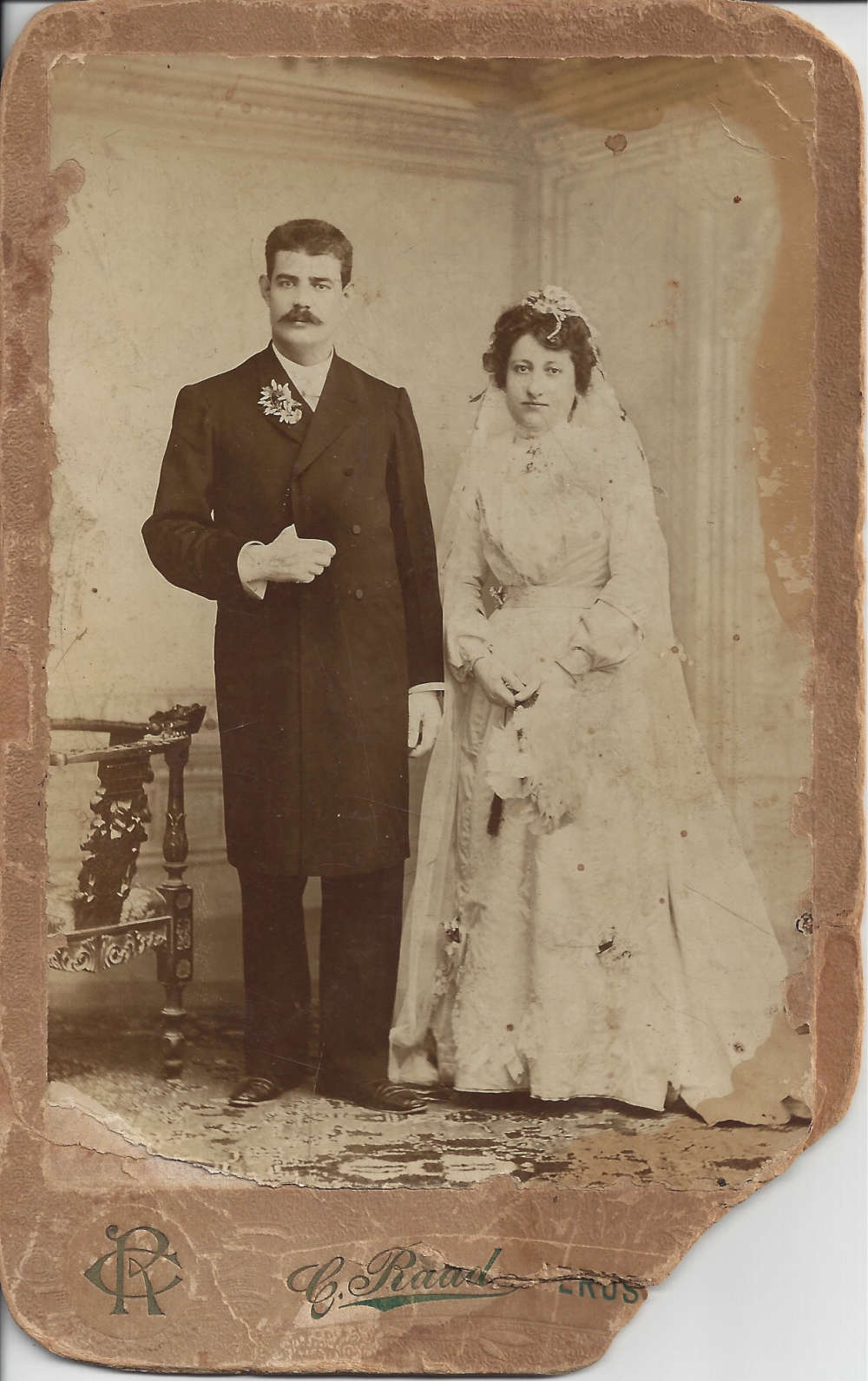

Before the outbreak of the First World War, Raad went to Switzerland to continue his studies under the photographer Keller. There he became engaged to Keller’s assistant, Annie Muller, whom he married after the war. In Jerusalem, the couple settled in Talbiyeh and had two children, Ruth and George.

The relationship with the Krikorian family was restored, and the two studios began to collaborate when Krikorian’s son, Johannes, who took over the studio from his father in 1913, married Raad’s niece. From that point on, Krikorian focused exclusively on portraiture whereas Raad also shot political events, archaeological excavations, landscapes, and daily life. During the war, Raad was granted special access to photograph Ottoman installations, operations, and officials.

Raad’s body of work comprises 1,230 glass plates, along with postcards, negative prints, and some film.

In the words of Samia A. Halaby,* Raad’s photographic eye is revealed by “the clarity and organizational neatness” that distinguishes his work. “Seldom is the background left thoughtlessly to chance. One has a feeling that his eye took a tour of the entire pictorial space before focusing on the essential subject. His organization of parts is like that of a painting. There is rarely an incidental fragment of something entering or leaving the field of view.”

After the 1948 fall of Jerusalem, Raad’s studio became inaccessible, located as it was in the dead zone that divided the city. Raad fled and eventually returned to the city of his birth where he remained until his death in 1957. His work was spared the destruction that befell so much of Palestine’s heritage thanks partially to the derring-do of an Italian friend who saved it and delivered it to Raad’s daughter, Ruth, who subsequently donated it to the Institute of Palestine Studies.

*“The Pictorial Arts of Jerusalem, 1900−1948,” published in Jerusalem Interrupted, Modernity and Colonial Transformation 1917- Present, edited by Lena Jayyusi.