When we woke up to a new reality on June 5, 1967, we realized that we were not ready for war or for an occupation. Many of us thought, however, that this occupation would come to an end as suddenly as it had begun, especially after the unanimous adoption of UN Resolution 242 by the United Nations Security Council on November 22, 1967. Of course many others were not as optimistic, considering that they had lived through the Nakba of 1948, and are still waiting for the implementation of UN General Assembly Resolution 194 that calls for the right of return of Palestinian refugees. The rhetoric of the occupying forces about “liberating Judea and Samaria” did not give much hope.

In the meantime, we had to be innovative and creative in dealing with this new reality. At the time, I was fully involved as a volunteer with the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), and we felt that our main concern was not only women, but children, youth, and the community as a whole.

With the support of Bread for the World, the YWCA had just finished the construction of a new building that included a section to be used as a hotel, offering the guarantee of a steady income that would allow the association to cover the cost of its activities and vocational school. When the war broke out, however, the building’s interior was not yet complete, although all the fittings and furniture were already stored in part of the building. The YWCA had been using two rented apartments on Salah El-Din Street, one that housed the administration, activities, and a hostel for girls, and the other a vocational school.

The first thing that worried YWCA general secretary Doris Salah was the new building. She feared that it would be taken over by the Israeli military forces, under the pretext that it was abandoned. In fact, the guard of the building had been killed during the war, although he was unarmed and all alone. Without hesitation, Doris took it upon herself to move the furniture and equipment of the two rented apartments to the new building to give the impression that the building was in full use. In the meantime, the contractor was able to resume work and finish the building.

♦ After the occupation of 1967, the YWCA in East Jerusalem served as the main gathering point for Palestinians of all ages who wanted to celebrate their heritage and engage in cultural activities. Its initiatives precipitated the building of new Palestinian cultural institutions among generation after generation of young Palestinians.

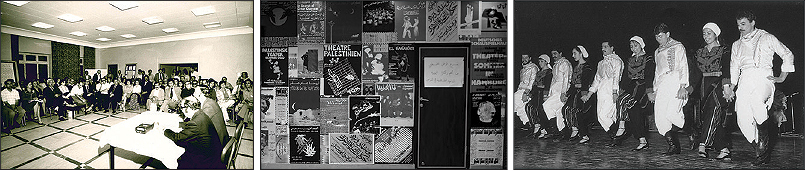

In no time the YWCA opened its doors and served as a haven for everyone in the community irrespective of faith or gender. Clubs for all ages were established; members of El-Jeel el-Jadid (the young generation) were able to enjoy a variety of programs such as music, art, and drama, as well as summer day camps until the YWCA was eventually able to buy property in Ramallah to run a sleep-in camp. Nadi el-Ghad (the Future Generation Club) laid the groundwork for training future leaders in civil society. Meetings, lectures, and panels on various issues were frequently held. There was no TV at the time, so the YWCA provided movies for children and occasionally for adults as well.

Members of The Mothers’ Group were very concerned about bringing up a new generation under occupation. They helped to plan programs for the children in order to provide an atmosphere of hope. The group helped to establish parent-teacher associations in the Jerusalem schools in order to guarantee cooperation between the school and the home. It also encouraged the promotion of local products and arranged for the first exhibit of local products with a special focus on traditional Palestinian handicrafts.

It was a time when there were no art galleries or music schools, so the YWCA worked with the schools to run art shows and competitions as well as musical performances, including school choirs. The YWCA itself hosted the Jerusalem Choir for classical music that performed during Christmas and Easter. For many years, Salwa Tabri directed the choir and Nadia Mikhael-Abboushi provided accompaniment. The choir eventually moved to Ramallah because of travel restrictions on the people from the remainder of the West Bank. At the same time, some of the talented young members of the YWCA formed a number of musical ensembles, and Rima Tarazi led a choir whose repertoire focused on Arabic national songs. One performance, in particular, was held in honor of the families of prisoners, including those who had been martyred during the hunger strike at the Nafha Prison in 1980. Another outstanding event was The History of National Songs performed by the choir along with a narrative about that history.

The dabka (folk dancing) group, trained by Saliba Totah, was one of the first in the country after 1967. The young men and women performed regularly on various occasions and also very often for groups who were staying at the YWCA hotel. In the absence of a national government at the time, with the occupying forces not assuming their responsibilities (under international law), it would not be an exaggeration to say that the YWCA was considered a center of culture and information. YWCA members as well as leading figures of the community were often asked to speak to foreign groups and to form study circles on the Palestinian cause. The YWCA even had its own human rights committee that documented violations and disseminated information before any of the civil-society organizations in that field were established.

At the request of UNRWA, the YWCA established preschools in Qalandiya and Jalazon refugee camps after 1967. The YWCA had already had extensive experience in the field after being one of the first organizations to work with refugees in Aqbat Jaber in 1948. Through the preschools, it was possible to work with the mothers in the camps and implement joint programs with YWCA members from Jerusalem and Ramallah, which was a great experience for both groups of women. Later on, young girls from the refugee camps were also able to join the summer sleep-in camps in Ramallah.

♦ The Oslo interim agreement of 1993 defined Jerusalem as a permanent status issue. Many Palestinian and non-Palestinian institutions began to move out of Jerusalem as the city became increasingly difficult to access for Palestinians from the remainder of the West Bank. As a result, the city began to lose its former status as a Palestinian cultural hub.

Shortly after these humble beginnings, in the early seventies, young committed members of the community from Ramallah and Jerusalem started a number of creative initiatives in drama, art, and music. Balaleen, the first theatrical group, performed in schools and municipal halls. All its members were volunteers. The script was written by the group itself to be pertinent to the situation, and the performances were in colloquial Arabic, which appealed to a wide range of audiences. Soon afterwards small groups mushroomed out of this first initiative, the most outstanding of which was El-Hakawati, which used Al-Nuzha Cinema as its base. Eventually the site became known as the Palestine National Theatre and hosted many drama groups and other activities.

It was the same with art. A group of committed artists started The League of Palestinian Artists in the early seventies, and their work focused on the Palestinian cause using symbols that were familiar to and understood by the community. The New Visions group emerged from the league and established Al-Wasiti Center in Jerusalem’s Sheikh Jarrah quarter. It was the first art center that provided opportunities for school children and members of the community to learn about art and attend art shows.

Also at the beginning of the 1970s, “committed songs” emerged to express opposition to the occupation, especially during the first Intifada. Mustafa al-Kurd and Al-Bara’em group were among the first names associated with this kind of music, and El-Funoun was one of the first dabka groups that eventually developed into a professional troupe. In the early 1980s, Sabreen musical ensemble was formed and was followed later on by a number of other individual initiatives. In the early 1990s the National Conservatory of Music was established by a group of musicians under the umbrella of Birzeit University. Soon after, other music schools were created, such as the Magnificat Institute, which is affiliated with the Franciscan order, as well as Al-Kamandjati in Ramallah.

Unfortunately after the Oslo Accords, Jerusalem, which was the center of most of the cultural activities, was greatly affected because the city was no longer accessible to the people who lived in the remainder of the West Bank. As a result, a number of initiatives, including Ashtar Theatrical Group, moved to Ramallah. In the meantime, other activities emerged in many locations throughout the West Bank. In Jerusalem, Palestinian centers such as Yabous Cultural Center, The Music Conservatory, Al Hoash Palestinian Art Court, the Palestine National Theatre, Al-Maamal Foundation for Contemporary Art, and Dar Issaf Nashashibi for Arts, Culture and Literature continue to contribute significantly towards sustaining cultural activities in Jerusalem. The regular book readings and book launches by the Educational Book Shop have been a source of political and cultural enlightenment, notwithstanding, of course, the contribution of Palestinian universities and community colleges who offer art and music programs, as well as the museums and other cultural centers on the West Bank.

My apologies go to all the young men and women who were involved in various initiatives and cultural activities but who are not acknowledged here. It would take a whole article to list their names and give them the credit that they deserve. However, this is a personal reflection and not formal documentation. Given the schools of music, art, drama, and folk-dancing, as well as the numerous talented artists, singers, and performers who have emerged over the years, the cultural aspect of Palestinian life has been a source of inspiration to help sustain the people under occupation, lift their spirits, and give them hope for a brighter future.

After fifty years, it has become clear that this is not an “ordinary” occupation that will be dismantled by a UN resolution. It is a settler colonial regime with an ongoing project of dispossession. Yet how can we lose hope when justice is on our side? And how can we lose hope when we see young children carrying their musical instruments and getting ready to join the orchestra? January 1, 2011, marked the debut of the Palestine National Orchestra under the slogan: “Today an Orchestra, Tomorrow a State.” Dare we hope?

» Samia Khoury is a retired community volunteer who devotes most of her time to writing reflections on the current situation. Her book Reflections from Palestine: A Journey of Hope, published by Rimal in 2013, is also the title of her blog: reflectionsfrompalestine.blogspot.com.